I made it to the canal! ...Learning about Anxiety in the Body

“Our symptoms can take up so much bandwidth that it’s easy to forget that symptoms point toward a problem–they’re a problem, but they’re not the problem.” -Britt Frank

GSS News this month:

I’m just about to wrap up my first in-person Somatic Movement series. Thanks so much to all the participants!

Coming up:

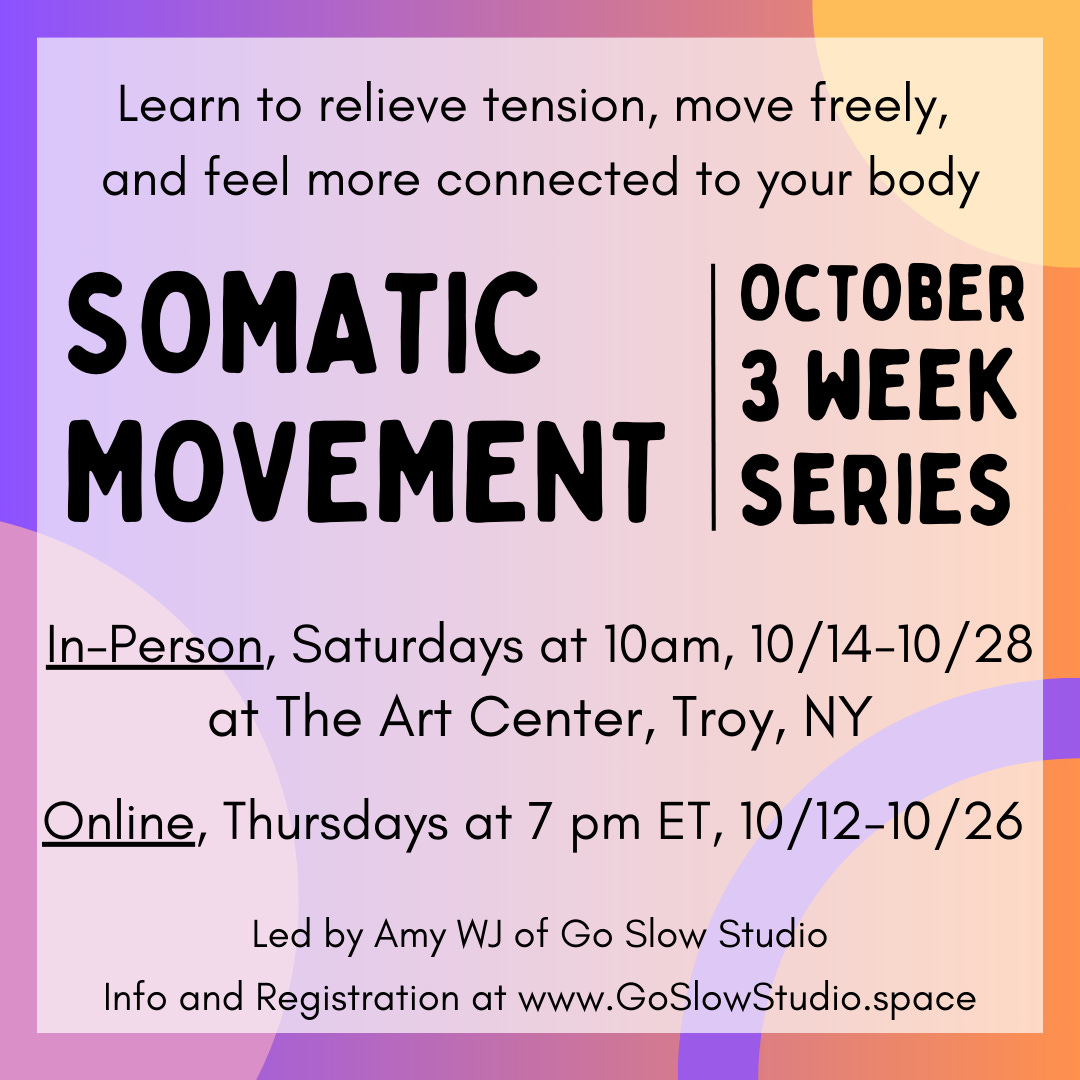

October: 3-week Somatic Movement series, Focus on anxiety

Online: Thursdays at 7 pm ET, 10/12, 10/19, 10/26, Sign up here

In-person: Saturday mornings at 10 am, 10/14, 10/21, 10/28. Held at the Art Center, Troy, NY. Sign up here.

On deck for November: A 5 week Somatic Movement series and a Zine workshop. Stay tuned for more info.

What I’m learning about this month:

Anxiety in the body

Following an experience I had with pain at the beginning of the summer, I began to think more about how anxiety manifests in the body. Anxiety seems to be part of our common conversation today and has even been called an epidemic, as explained in this 2018 article (and we know it has only gotten worse since then). With the help of two books, one I stumbled onto with perfect timing, and the other that had been in my stack for awhile, I made more sense of my experience, learning about anxiety and how somatic tools can help us better understand and move forward even when we’re experiencing it.

The experience was this: Earlier this summer I began to have days where I felt fibromyalgia pain creeping back in. Last fall, after a summer of grueling pain and fatigue, I worked with a great rheumatologist, who after ruling out Lupus and the like, prescribed that I focus on cardio and sleep and recommended I get off my anxiety meds (he finds the side effects just aren’t worth it for a lot of his patients). I took his advice and not long after, the pain receded. I celebrated and breathed a sigh of relief that it had been the meds that were causing such debilitating pain and fatigue. And yet, after 6 months of mostly feeling good, the pain began to rise. I cried with frustration and fear–I couldn’t go back to that state, I wasn’t ready to lose the plans I’d made for what I wanted to do this summer. It was clear it wasn’t all in the meds (though the extreme fatigue has not returned), so I thought about other patterns that may have been contributing. I was facing some stress as we neared the end of a major home renovation and I’d had a busy month in terms of my Movement Teacher Training. And while I was still taking daily walks and staying active through housework and gardening, I hadn’t been focusing on cardio.

Back when I started with my doctor’s advice, I had the sense to start small. I set myself the small goal of getting at least 10 minutes of cardio every other day. I would dance to a few songs or make my daily walk a brisk one. As I began to feel better, the goal stretched to 20 minutes and included jogging or a short aerobics video. But then I got the flu, and then we traveled, and then I got sloppy about my routine. So when the pain came back, I knew I needed to return to my small goal–10 minutes of intentional cardio. On a day when I was feeling truly awful but had still dragged myself to work, I set my sights on the canal. I knew from the previous fall that the distance from my office to the canal was one I could cover at a brisk walking pace in 10 minutes. I was pretty sure I wouldn’t make it, so I gave myself permission to slow down and turn around as soon as it felt like too much. But then I made it. I approached the bridge with tears in my eyes and a huge smile on my face. I made it. It was such a minor accomplishment but felt so significant when I’d been sure I’d need to turn back blocks before. The next day, I felt better. And then the next day I made it to the canal again, still feeling it was a significant accomplishment. I’d gotten there and been reminded that by taking this minor step I had some control over my situation.

The very next weekend, wandering the library, I happened upon a title that caught my eye–Move the Body, Heal the Mind by neuroscientist Jennifer Heisz. I sat down to read it right there and found exactly the science behind what I’d experienced!

So why is a tiny amount of exercise a tool for managing anxiety and pain? In short, it’s because it helps you experience the stress response in a way that feels safe. Anxiety is essentially a warning mechanism in your body. When your brain senses some kind of danger, your body responds with hormones and physiological shifts that prepare you to fight or flee. However, this response can be triggered whether the threat is imminent danger or just something your brain interprets as dangerous or stressful. If we experience prolonged stress, whether we’re living in a dangerous situation or repeatedly in situations where we feel stress or like things are outside of our control, our brain and body respond by feeling anxious. Anxiety at its core is the feeling that you’re not safe.

In her book, Dr. Heisz talks about this mechanism and how exercise, even gentle movement, can help. Exercise activates the same stress pathways as anxiety but does so in a way that you are in control of, therefore in a way that can help you feel safe. Heisz writes, “This not only increases your capacity for exercise but also upgrades your body’s comfort zone for other things in life.”

However, it’s important to know that you have an exercise threshold. Heisz recommends finding the “just-right” amount of exercise for you. Too much or too intense exercise can overtax the stress response making anxiety worse. I learned this first hand when in the spring of 2022, before the worst of my pain and fatigue, I joined a Zumba class. The first week felt great–I was on top of all the moves and dancing my heart out. But as the weeks went on, I couldn’t keep up. I did the moves half time and then I couldn’t complete a class. At the time, I couldn’t understand why it was getting harder, but now I see it was reflective of this threshold. A full hour of high-intensity exercise was overtaxing my stress response, putting my body on high alert, and weakening my ability to recover.

Heisz’ message is to start small. Many people experiencing anxiety and other mental health or chronic pain issues may feel uncomfortable with the idea of moving their bodies. Not to mention, if you over-do movement at the start, you’re less likely to keep it up. Starting with light movement, such as a 10 minute walk, can help a person get in touch with their own body and begin to feel safe in it, which is key to quelling chronic anxiety, and for someone starting out, it can be enough activity to trigger the neurochemicals that help the brain recover from the stress response. In her lab, Heisz has studied compounds released by cells after periods of exercise. One in particular, a neuromodulator called BDNF, bathes the brain post-exercise adding protection to brain cells and turning off the stress response. Another compound, called Neuropeptide Y (NPY), is considered a “resilience factor”, found in higher levels in people who go through trauma but don’t develop PTSD. No matter your base level of NPY, the body can create more of it through exercise. Because of this, Heisz has found increased benefits when combining exercise with anxiety therapy, such as going for a post-session walk. For the average person, Heisz and her colleagues have identified that just 30 minutes of light to moderate intensity exercise three times a week is “enough to soothe your anxious mind” and get the benefits of these neurochemicals.

Once we feel safer in our bodies, we can then become more aware of our responses and what’s happening in our bodies. If we’re on high alert, our brain is focused on the anxiety itself. It’s not available to reflect on what’s happening in the body, and it’s nearly impossible to learn new things. Awareness is essential because when we can reflect on our patterns we can then make choices and learn new patterns that help us feel more comfortable and engaged in the moment.

A Lifekit episode that’s been in my podcast queue since May, but which I finally listened to recently is entitled, “What to do when you’re feeling anxious”. In it, Marielle Segarra interviews Britt Frank, a therapist and the author of The Science of Stuck.

Frank discusses that anxiety is the brain trying to make us aware of something–it doesn’t feel safe. If we can regard it as an indicator light, we can then pay attention to it and respond. She acknowledges there are a lot of different factors that go into our anxiety: genetic, societal, situational, etc. By slowing down to pay attention we can find space to become aware of what these factors are and then make choices about our situation that can help. In her work she’s often found that anxiety is displaced grief, or not acknowledging truths. It’s not essential to fully figure out your underlying issues, and may not be practical for you to make big changes, but even recognizing that you have choices can be a powerful first step.

Stopping to pay attention to your anxiety is not always an easy thing to do, so Frank recommends practicing it. She explains, “We’re taught ‘stop, drop, and roll’, but with mental health issues, we’re not taught to practice for when the crisis hits. We’re taught, you’re fine, you’re fine, you’re fine, oh no, you’re not fine”. So an anxiety “fire drill” might look like making a list of things and people that make you feel safe and then engage with them so that you’re ready when you do get there.

This practice is key. For those of us who are chronically stressed/anxious the pathways to the stress reaction are well-worn. We may be hypersensitive and feel like we’re always on guard. So we have to work to make and reinforce new pathways that support us.

In next month’s newsletter, I’ll continue this thread on anxiety, sharing some lessons from another book, Minding the Body, Mending the Mind (similar title, different decade). In the 1980s, the author, Dr. Joan Borysenko, helped found the Mind/Body Clinic and pioneered research in behavioral medicine at Harvard. In the book, she details ways to help raise awareness of your own body and how that awareness can help not only quell anxiety, but improve your overall health.

I was also curious what a Somatic Movement series focused on anxiety would look like, so I decided to plan one. Over 3 weeks in October we’ll work in the Hanna tradition of Somatic Movement. If you’ve taken a class with me, it will feel similar. However, there’ll be some additional focus on the breath and exploration of the withdrawal response as we work on opening the front of the body. Offered in-person and online at this link.

Interested in reading these books? Use this link to access my bookshop.org page, where you’ll find these and other books discussed in this newsletter. Your purchase through this link helps support this newsletter!

A note about this newsletter: 2nd Sundays and maybe more…

This is the 8th month I’ve put this newsletter out, and I thank you so much for reading and learning along with me! It’s felt good to be writing and sharing with you all. I had set myself a goal of just getting it out sometime at the beginning of each month, so now that I’ve done that, I recognized that picking a specific day would be helpful for both myself and you readers. You can look for this newsletter in your inbox on the 2nd Sunday of each month. As I move forward with forming and defining my Go Slow Studio work, I’d like writing to continue to play a bigger role. In the coming months you may see additional writing come out as well as opportunities to engage with it through other features in the substack plane.

The Question Box:

When I was a teacher, I had a box out for students to submit questions/suggestions. This was especially helpful during the Reproductive System unit in Anatomy and Physiology 🙃

Writing my above-mentioned book, The Pelvic Floor…, was such a great and empowering way for me to research a topic. I want to keep that momentum going by continuing to learn and write about topics people want to know about.

Have a question or suggestion for a topic–submit it to the question box here!!